To close off the semester, I thought I would interview a local psychologist, Professor Marvin McDonald from Trinity Western University, on the topic of memory. His input has always had a big role in my life, if you might have guessed by our shared last name, and I enjoyed asking for those nuances only someone with decades of experience in the field can provide. Please enjoy!

Category: Free Inquiry (Page 1 of 2)

This is the category to apply to your Free Inquiry posts.

My final interview this semester I met with Nick Atkinson, a colleague in this program who has spent time honing his memory in the context of theatre. In this discussion, we talk about Nick’s experience with memorizing lines and how he thinks teachers can incorporate this knowledge and experience into the classroom.

For theatre, he breaks down memorizing lines into three stages.

Stage One: Script

The first stage involves identifying key segments of the script and repetitive rehearsal of the words without too much affect. As he mentions, actors need to memorize the words in an affectively decontextualized manner, the idea being that they need to know the words but not overdetermine delivery in the same process.

Stage Two: Blocking

This stage involves blocking the scene, which couples the physical, sensorimotor components of act scene with the act of remembering and recalling the words.

Stage Three: Deep End

The deep end involves trying out the lines without any support beyond calling for lines. What this stage does is force students to recall the words without any aids beyond memory, thus allowing actors to practice in a context as close as possible to performance. That they must continue in the moment, calling for lines without breaking character, allows actors to build deep familiarity with the flow of the scene and practice recall in a context close to performance standards.

Transferring to the Classroom

In the classroom, Nick sees the emphasis on multimodality transferring most of all. As a learner, outside of his own acting, he has found notebooks to be most useful for notetaking. “Having to physically write things out helps,” he clarifies.

To make this work in the classroom, he suggests teachers could record their lectures for students to play back should they need. To avoid potential legal issues, he imagines that teachers could wear a microphone around their neck, thus preventing the possibility that students’ voices might be recorded.

Thank you, Nick, for your insights and stories!

This week I was able to speak with another colleague in the Secondary PDP Program, Andrew Board. Like in my interview with Kolton, I asked him to reflect on his own experiences with memory. Despite some similarities, our conversation went in a unique direction with a particular focus on the role and place of memory in designing curriculum to meet the needs of all students.

After speaking with Andrew, I feel more confident that this Ed program is preparing us to reflect in productive ways on both our own learning experiences and those of others. By combining these directions of attention–one internal, the other external–we can maximize our utility as educators.

Please enjoy the conversation!

Working on the bestiary is harder than I expected, especially during classes. Committing animals and images to memory not only takes time, but also attention to detail. With each of the critters, I have to memorize more than the name to make them useful; I also have to memorize their visual characteristics. Since I have little experience with biology or attending to specimens with such detail, I am trying to pay attention in ways that will stick in my mind. Needless to say, the processes teaches more than just a technique for memorizing names; it also trains me to notice things I otherwise would ignore!

Here are the next ten in my bestiary:

Alligator

Amur Leopard

Ant

Aorta

Appenzeller

Aquanaut

Arapaima

Ascaris

Atlas

Aussiedor

This week, I was planning to work on my bestiary technique for memorizing names, but I had the chance to interview a fellow student teacher on his thoughts about memory instead.

Over the course of twenty minutes I asked Kolton seventeen questions, and his answers sparked some intriguing insights about the utility of memorization techniques in the contemporary world. Here are a few highlights:

Personal Techniques

His own techniques tend to be fairly semantic. Although he is capable of visualizing in his head, he prefers to study for exams using traditional methods. Kolton takes notes by hand and transfers these to his computer later, each step seeming to help him remember more. Once on the screen, he can quiz himself by covering up the computer. He also enjoys rehearsing the ideas in his head as though he were explaining the concepts to another person. In the process, he discovers what he struggles with, allowing him to go back and review those areas.

Kolton also enjoys using the keyword method for learning vocabulary in other languages, even if he did not know the name for this technique until recently. The technique has come in handy for learning Spanish vocabulary in particular, and he enjoys taking parts of words and relating them to other, similar-sounding words that can anchor the meaning in some way.

Teaching Memory Techniques

Kolton has a pragmatic view of memory techniques: if they work, use them, but otherwise, don’t stress! He will certainly pass along methods, if he thinks they might be useful for students, but he will offer them as a possibility for them to try if they like it.

The technique he thinks may be most useful to share with students is the keyword method. In the context of language learning, for example, students would do well to commit vocabulary to memory, since automaticity is so key to fluency.

When I probed him further about other contexts, he suggested that the loci method could be a useful technique for learning procedures as a barista at Starbucks. New employees could commit steps to memory in a particular sequence by anchoring them to familiar locations. Cool idea!

Memory in a Digital World

While Kolton believes that memorizing a large body of facts is not as important today as it might have once been, he does see a place for memory in many practices still critical today. Some of the contexts we discussed include presentations and job interviews, both of which illustrate circumstances in which you cannot access external devices to prompt your recollection of details. Knowing the facts intimately is also important when engaging youth. The range of incomplete and inaccurate positions are impossible to check without some grasp of a range of facts.

Kolton also expressed how important it is to protect and sustain local Indigenous knowledges, especially languages. Global pressures make it hard to sustain small communities, but diversity is part of what makes global engagements and exchanges beautiful. In other words, to safeguard strong intercultural engagements, we must protect the cultures that sustain diversity.

Whole Conversation

Kolton has graciously allowed the conversation to be uploaded. Here is the whole interview for those who want to get a better sense of Kolton’s insights:

Thank you, Kolton, for your thoughts and ideas!

How do you make a useful bestiary? First, it needs to have vivid images. Second, it needs to have images related to letters of the alphabet. I will be following Lynne Kelly’s method, as described in her book, Memory Craft:

So I decided to create a bestiary based on the first two letters of a name. Instead of using just one letter of a visual alphabet for all ‘M’-name people, I would be splitting them into ‘Ma’, ‘Me’, ‘Mi’, ‘Mo’, ‘Mu’ and ‘My’-name people. Every animal has a significant feature: Aardvarks have fleshy noses, herons have elegant necks and macaws have heavy lines around their eyes. I would instantly know what animal to imagine during our initial conversation, and this meant the key feature I was looking at when I met a Mary or a Martin or a Max would be the same–the lines around their eyes.

Once I was sure I had memorised the first two letters, I could then reinforce the rest of the name at my leisure. My system would work for any name or surnames. In fact, the bestiary works as a memory aid for anything you can spell. I often use it to remember an unfamiliar word or the name of a cafe for a meeting.

I created a list of all possible word beginnings–‘Aa’, ‘Ab’, ‘Ac’, ‘Ad’ etc–which became disturbingly long, especially when the first letter was a vowel. I ended up with 264 pairs. If I couldn’t find an animal starting with those two letters I sought out a mythological beast, a plant or even (when desperate) an object. Medieval bestiaries were fairly relaxed in their definition of an animal, with mythological beasts and the real thing all merrily mixing, so I felt justified in stretching the concept just a little further.

Lynne Kelly, Memory Craft: Improve Your Memory with the Most powerful methods in history (pp. 25-26)

For my purposes, I will try to stick to animals, but I can see what Kelly means by how difficult this task can be. Without knowing many animal names off the top of my head, I struggle to think of creatures for the variety of combinations. That being said, I might have an advantage: I am combing through the Oxford English Dictionary. Whereas Kelly could not find a beast for the “Ae” combination (p. 26), I can resort to prehistoric animals.

To keep this task manageable, I plan to create a list of ten animals each week. Over time, after having amassed the whole list, I will memorize it and see how it works. Clearly a long term project! Here, at least, is my first ten:

Aardvark

Abyssinian

Acaleph

Addax

Aetosaur

Affenpinscher

Agama

Ahi

Ai

Ajax

Akalat

The next stage of my memory exploration will be a highly practical side of teaching: remembering names.

My experience with this practice is quite inconsistent. At my work I try to remember names of regular customers as best I can, but sometimes they do not stick. My recollection of how accurate I tend to be is surely also problematic, but I am pretty sure I struggle with common names, especially if I know a lot of people with that name from the same context. Likewise, I have struggled more recently to remember names with the introduction of masks indoors.

What these difficulties suggest to me is that I need to find strategies to address two issues:

- To connect particular names to particular people.

- To connect them to features that are visible outside of masks.

Ransom Patterson has some advice that may come in handy:

- Use the person’s name in conversation

- Rehearse the name (practice retrieving it)

- Use mnemonic devices

I struggle with the first approach because I find saying people’s names during conversation somewhat awkward. Lynne Kelly suggests in Memory Craft, however, that she turns it into a game with each new acquaintance, a practice that likely allows her to say others’ names without social embarrassment (2020, p. 28).

I have already started working on the second approach with student names during observations. So far the practice has been quite successful, though I still forget to do so occasionally. If I get a chance to write down student names in a notebook, this practice helps as well.

The only practice I have not developed yet is a mnemonic system. Simple ones might involve the keyword method. The difficulty with this is how time consuming the process is to commit a name to memory on the fly. Lynne Kelly has what sounds like a more durable and consistent system, however–a “bestiary” (2020, p. 25)–which allows her to create a visual system based on the first two letters of every name. When meeting people, she can just memorize the first two letters and commit the rest of the name to memory later on at her leisure (p. 26).

What a large project!

For this reason, the rest of the semester I will build my names bestiary ten letter-combinations at a time, providing small illustrations or descriptions each week. Over time I hope to develop a large, sophisticated system with which to commit names to memory for the rest of my life.

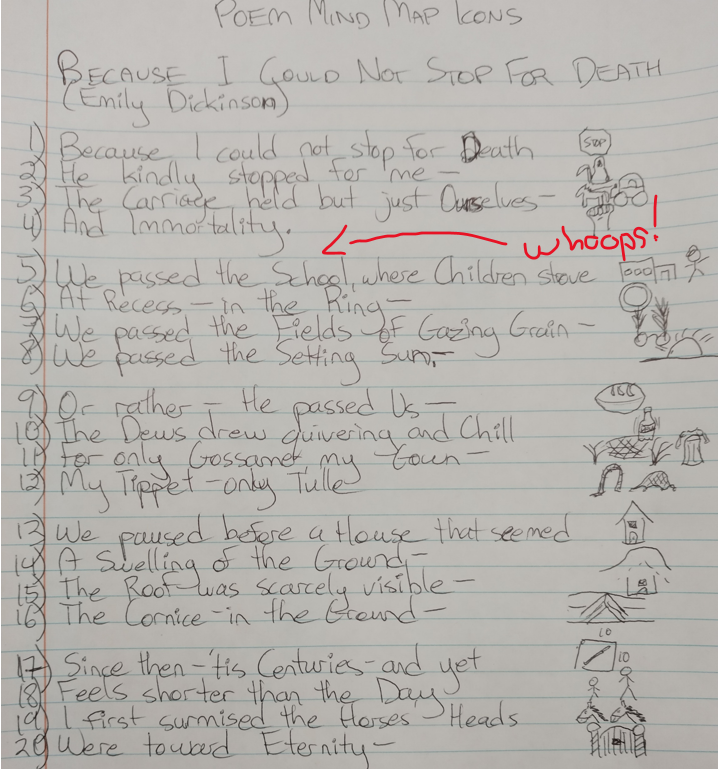

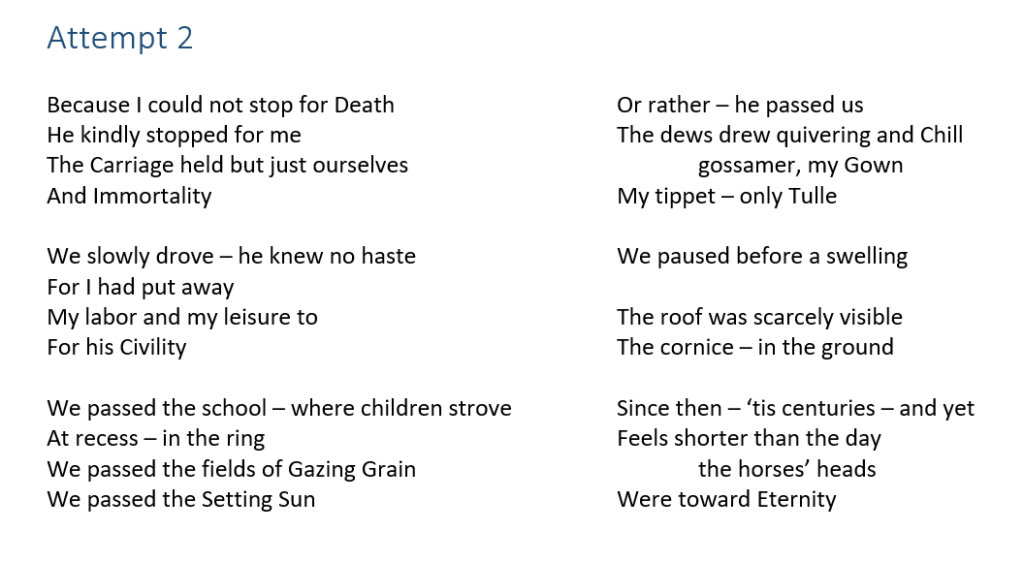

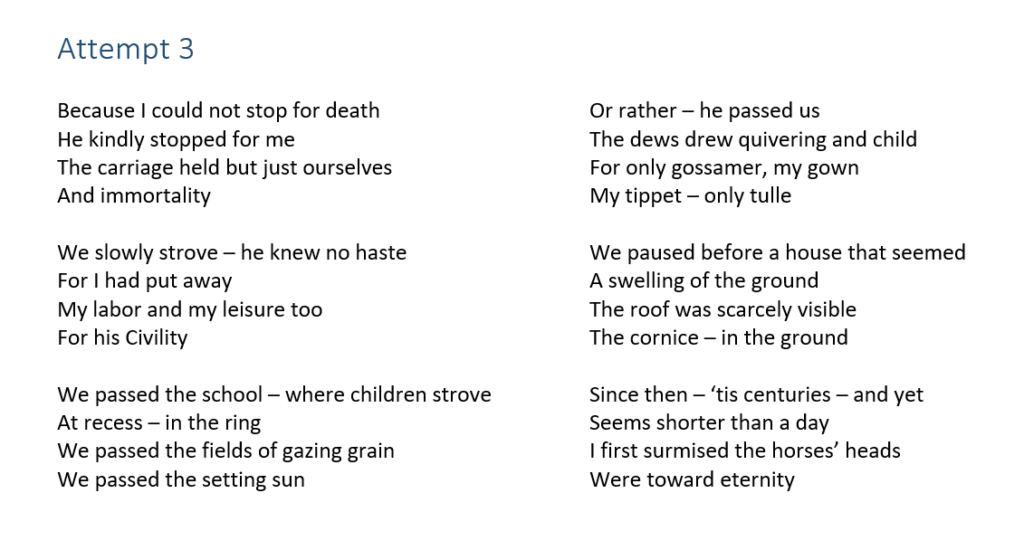

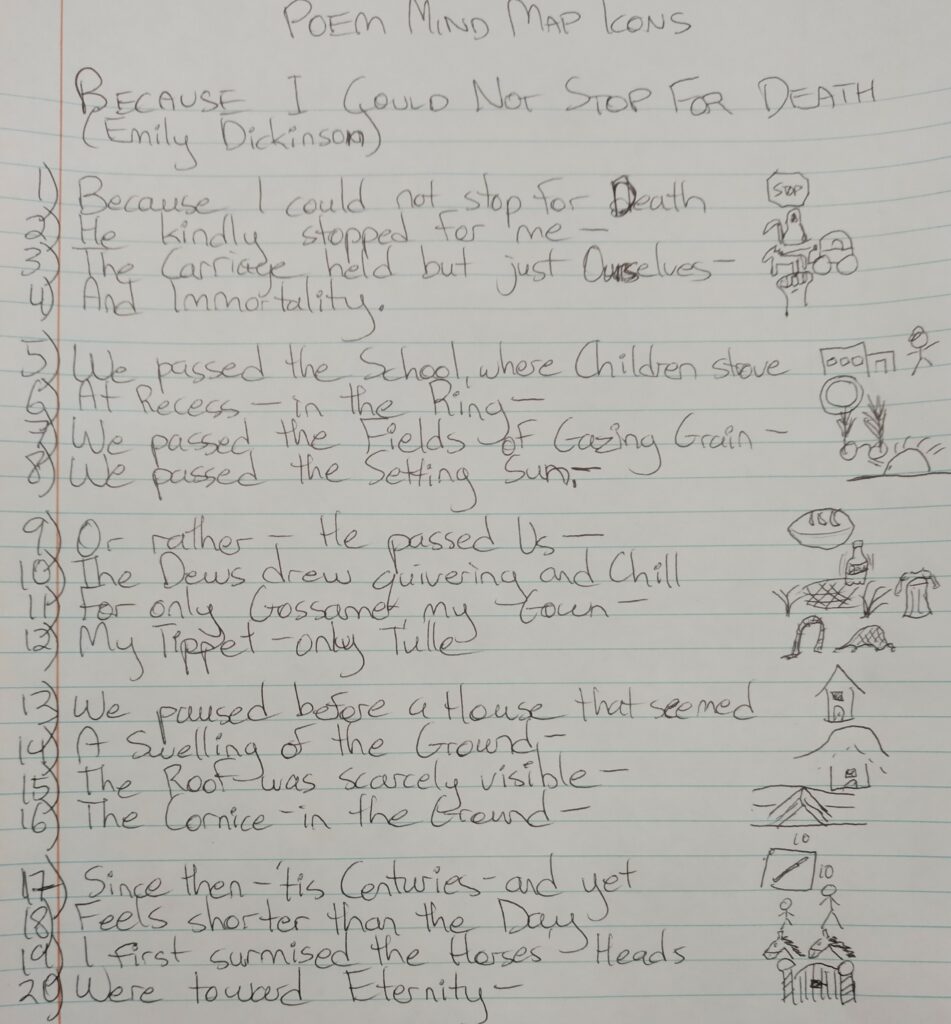

Memorizing Emily Dickinson’s Because I Could Not Stop for Death has proven to be difficult for a couple reasons. First of all, I missed an entire stanza when first creating my series of icons! This made my mind map fairly awkward. When I first placed the images in a certain order, they became somewhat fixed in place. Trying to augment the journey has proven difficult, and I have had to add a loop through some mental gymanstics.

Second, I have found the process of connecting precise words to the icons more difficult than with Robert Frost’s poem. Two factors seem to be at work. On the one hand, Dickinson’s poem is far more abstract than Frost’s, meaning the icons are more difficult to anchor to the terminology. I have to spend more time establishing strong associations between the images and language because the words are not necessarily as evocative by themselves. On the other hand, because I spent little time memorizing word order, the lines come out a little garbled on occasion. Rote repetition, which I used to memorize Frost’s poem, seems to provide a better anchor for linguistic precision. Turning each line into an image later on simply reinforces that order, and the spaced repetition cements them in my long-term memory.

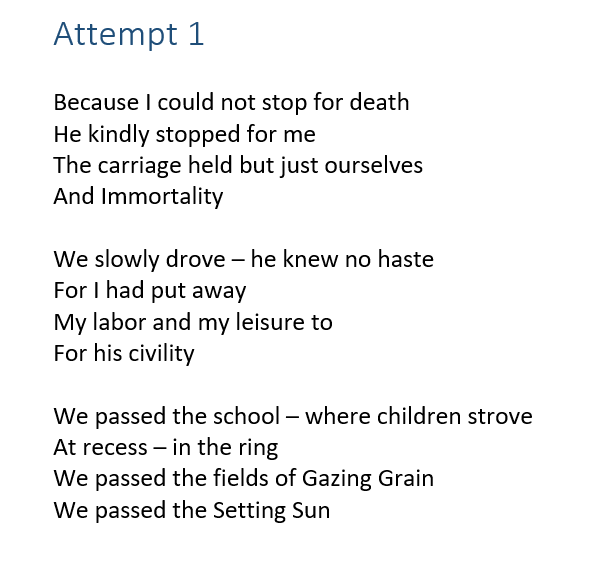

Here are a few attempts over the past week:

Once I realized what happened with the second stanza, I played around with the imagery of the carriage and made it run slowly. The “slow-motion” cadence now cues me and I can keep most of the other imagery in place.

The second time through, I realized that my icons were not working as well as I’d hoped, especially in the fifth stanza. For some reason I had mixed up the order of the ground swelling and the house, thus confusing me about which line should correspond with “swelling.” My icons were not particularly strong in this case. The other issues showed up in the fourth and six stanzas. My hunch is that the images were so strong that they ironically drowned out the more abstract words. To “surmise” something is hard to see; the same is true of subordinate conjunctions like “for.”

At this point, I have the poem mostly in mind. I will need to try it out a few more times before it sticks, but the wording will work with time. Needless to say, I have learned a great deal about how to commit poems to memory for the long term. By combining two techniques, I should be able to do so confidently with most any poem.

Digits of Pi

Memorizing the digits of pi with the loci method has had a lasting impact. I still recall the numbers precisely in the locations I have placed them. I was even able to add three numbers in relatively little time. Should I need to, I could extend this pattern indefinitely with locations in the building:

- Bathroom – metal 1

- Recycling – cardboard 4

- Elevator door – crowbar 1

- Lobby sign – springing 5

- Lobby bench – sleeping 9

- Showroom welcome desk – shouting 2

- Showroom cash drawer – crinkled 6

- Supervisor cupboard – springing 5

- Hallway door handle – dangling 3

- Mezzanine keypad – popping out 5

- Moen no-charge parts – hiding 8

- Delta tub spouts – spinning 9

- Aluminum roof stacks – slotted in 7

- Grohe cartridges – wrinkled 9

- Shower rods – hiding 3

- American Standard cartridges – dancing 2

- Toto Washlet adapters – stretching 3

- Lunchroom fridge – shivering 8

- Lunchroom locker – springing 4

- Lunchroom television – pixilated 6

- American standard faucets – cutting 2

- Laundry faucets – smoky 6

- Flush valves – spinning 4

Poetry: Frost

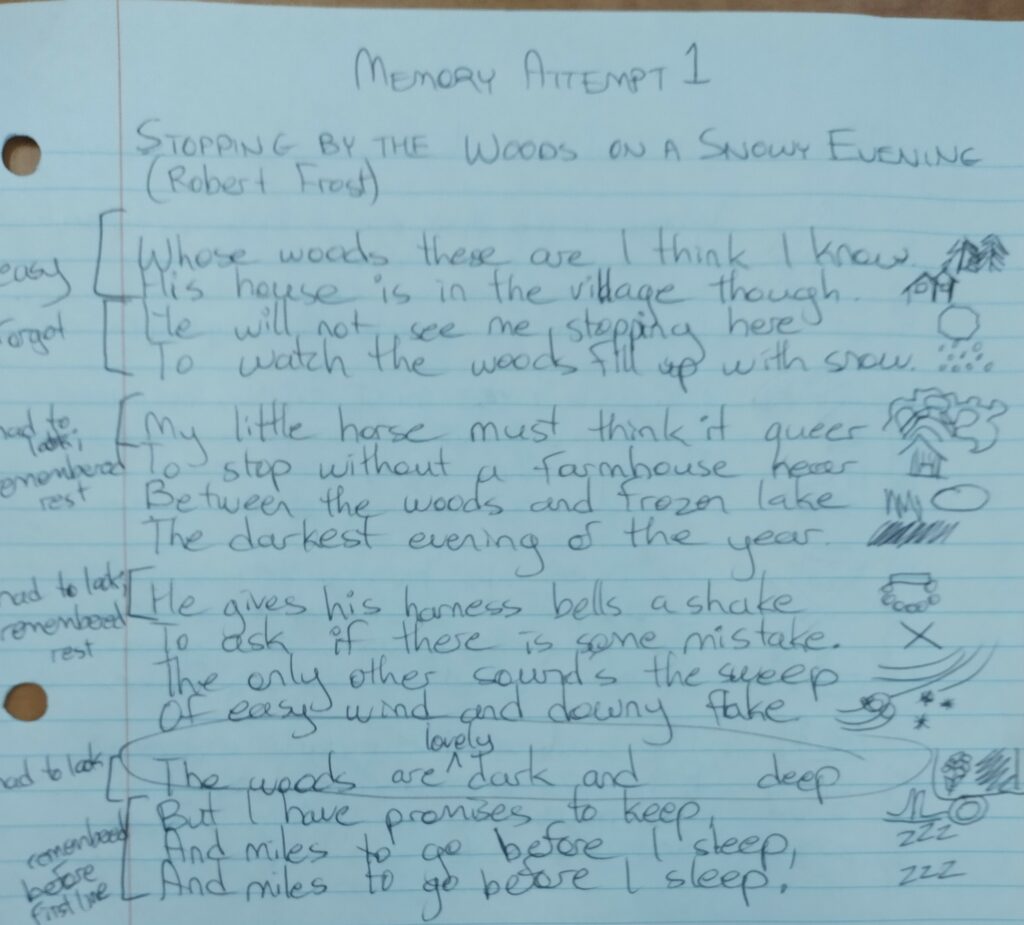

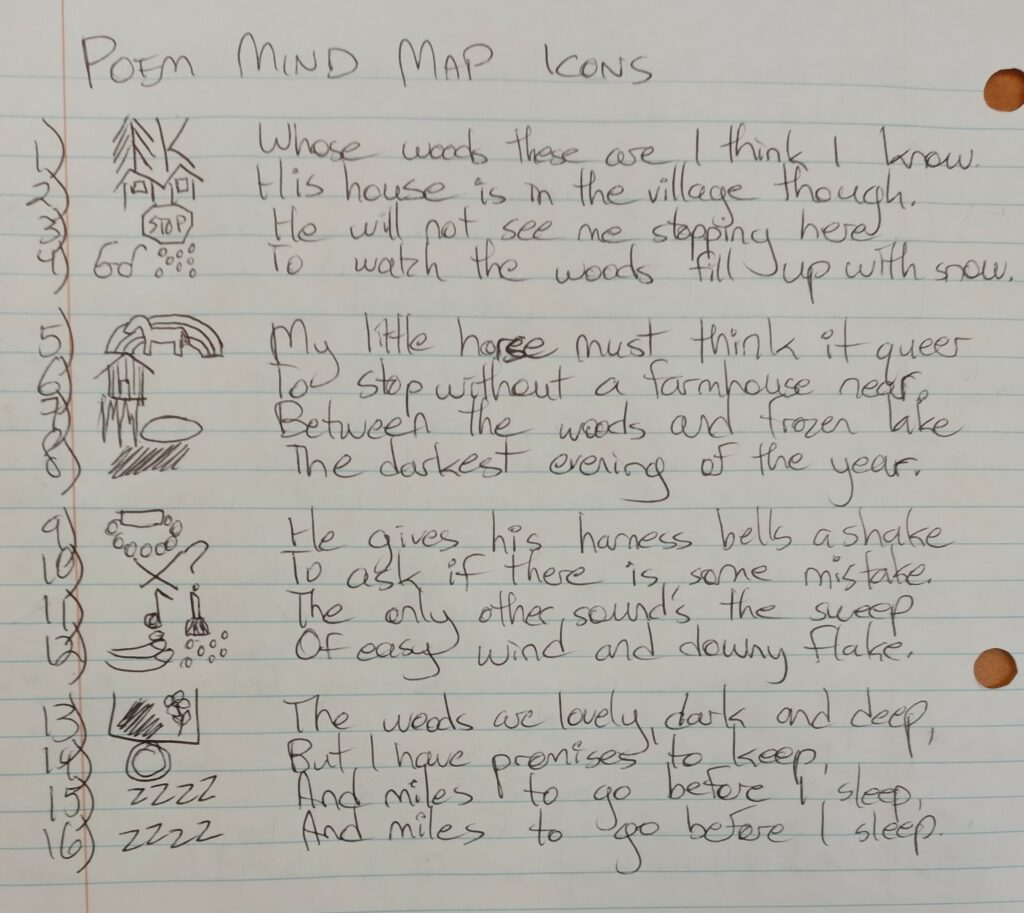

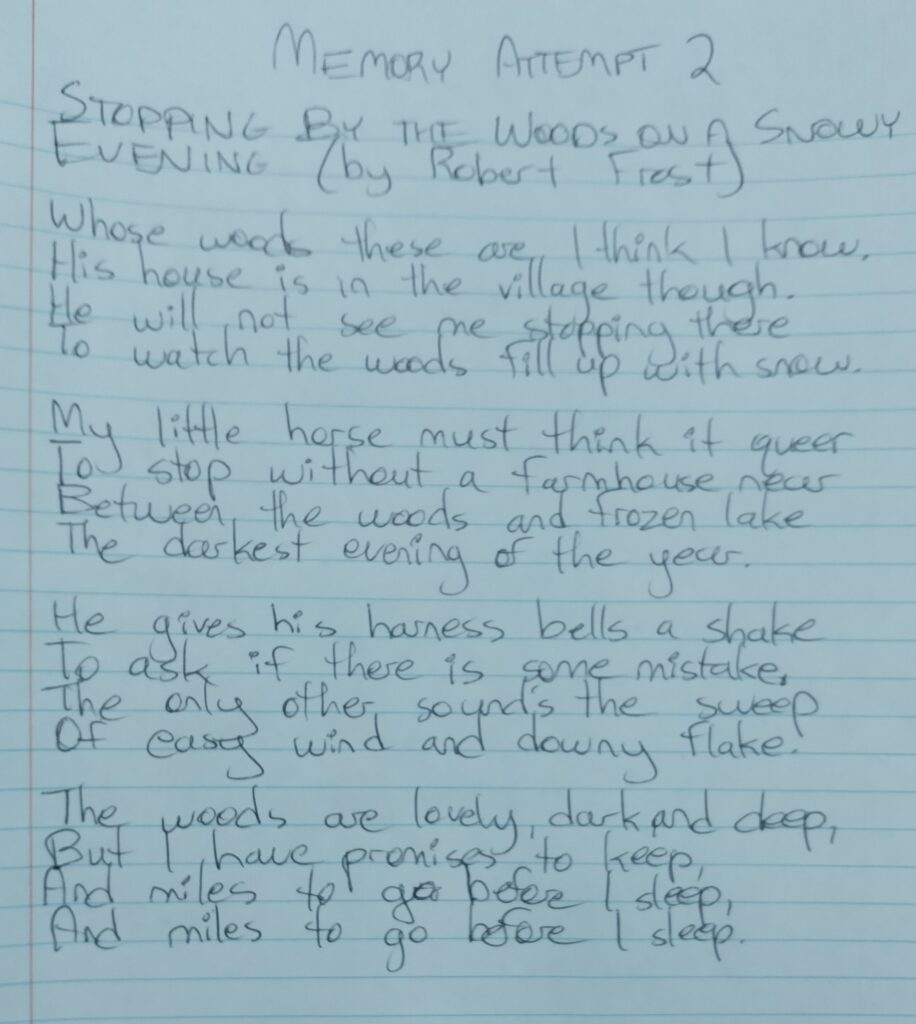

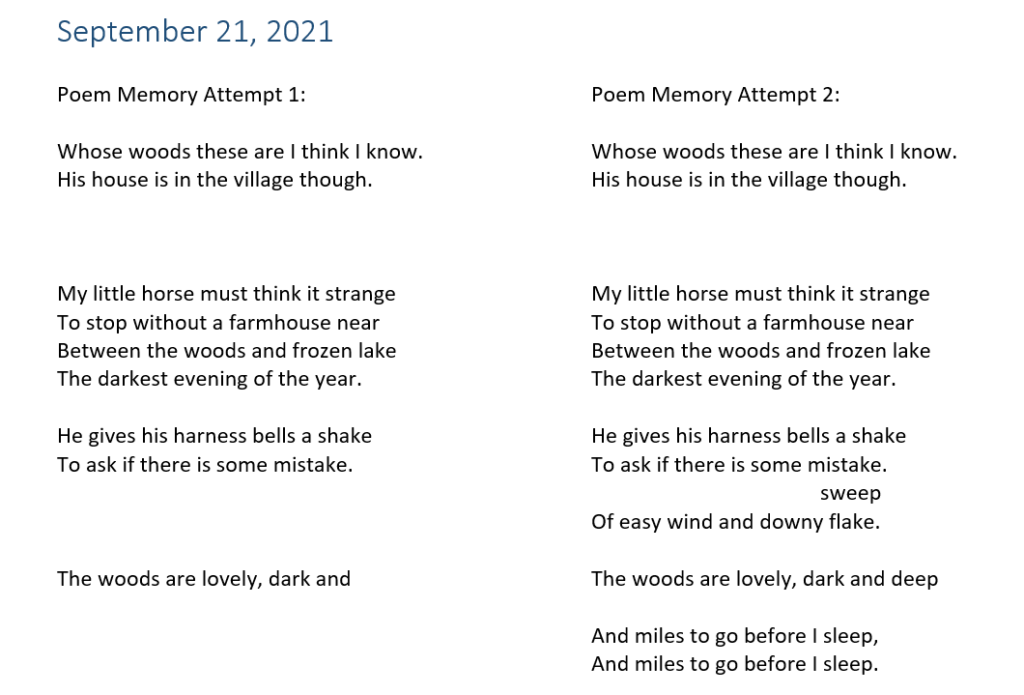

Memorizing poetry remains difficult for me. My recall of Stopping by the Woods on a Snowy Evening by Robert Frost was spotty to say the least. I was able to remember the first two lines without a problem, and the second two came after a bit of thought, but I needed to check the poem to recall the first few words of each stanza. The rest seemed to come relatively easily with these first few words. This suggests to me that I have the stanzas largely memorized as units, but I struggle to link them together.

For this reason, I am going to start associating simple icons with each of the lines of poetry and imagine them interacting in my mind. I will also create a simple mind map using the method of loci to place them.

Locations and icons

- Front door to building: trees and K’s shooting at door and breaking the windows

- Community book library: little community free library is shaped like a house, and thousands more being popping up next to it like a village

- Place where smokers congregate: I use a stop sign to smash things

- Bank windows: I take off my glasses and see trees inside with snow filling up and people struggling to get out

- Coffee shop: a tiny rainbow horse crashes out of the windows

- Red barn market: a red barn falls onto the store and crushes the store

- Walkway between trees and pond: I slip and fall because of all the ice between the trees and pond

- Exercise room: it is pitch black and I cannot see anything inside

- Coffee shop: a horse carriage with bells ringing crashes into the coffee shop during an earthquake

- Crosswalk: a big question mark and a large “X” are sword fighting above the traffic

- Bus stop: a guy sweeping the bus stop rigorously while whistling produces notes above his head

- Four-way stop: the guy gets blown easily a four-way stop with snow coming down

- Hotel: a forest of flower trees emerges, pushing a dark shadow off the hotel, only to fall into a large, deep hole

- Bay: I find a giant ring on the bay wall railing, and I try to hold onto it as it floats into the sky

- The sky: I look up and see “Z”s floating around in the air above my head (this counts for two lines)

With these locations and icons, I was able to recall the poem relatively easily:

Poetry: Dickinson

The next poem to memorize will be Emily Dickinson’s Because I Could Not Stop for Death. I will start by forming icons for this poem from the start. Perhaps this method will take longer, but I can imagine it will stay in my mind longer. Here is my start.

With this piece completed, I will start building another mind journey with locations to anchor each icon. Once those structures are complete, I will memorize the poem and test my recall of it next week.

On September 21st, I could only remember some lines of the poem. The ones which were most difficult for me to memorize last Friday, like the second stanza, were the easiest to recall this time around. The final stanza seemed strangely opaque, even though the last two lines did return to me after a little thought. Overall, my memorization technique of brute force appears to have been insufficient to lock the poem in mind for the long term. Thinking about the poem allowed me to recall through rhyming associations, and for some reason “easy wind” and “downy flake” emerged over time, but I had no mental structures within which to place the images. Were I to have waited longer, I would likely have forgotten much more of the poem.

After noticing how limited my brute force techniques are, I began my first attempt with the method of loci. Following the instructions, I decided to use a building I know quite well: my workplace. Because of all the time I have spent searching for items in various nooks and crannies there, locations and pathways are easy to construct and recall in mind. For the sake of brevity, I have started with just twenty locations. In the future I plan to add more.

- Basement bathroom mirror

- Recycling room

- Parking elevator door

- Upstairs lobby sign

- Lobby bench

- Showroom front desk

- Cash tray drawer

- Showroom supervisor’s cupboard

- Hallway dead end door

- Mezzanine keypad

- Moen no-charge parts

- Delta tub spouts

- Aluminum roof stacks

- Grohe cartridges

- Shower rods in the corner

- American Standard Amarilis cartridges

- Toto Washlet adapters

- Lunchroom fridge

- Lunchroom locker

- Lunchroom television

To test how well these work, I placed the first twenty digits of pi into the locations (3.1415926535 8979323846). With each one, I used dramatic, interactive imagery to ensure that they remain vivid. For example, with the first location, I imagine bashing in the mirror with a giant, metallic number one:

I also tend to associate colours with my numbers, meaning they stand out clearly from the surrounding. Although it took nearly 30 minutes to construct the route, using it was easy. Unlike with the brute method approach, I felt generally calm as I traced the digits. Each time their images came to mind the moment I arrived at the relevant place, almost as though I were simply finding them rather than remembering them. What a breeze!